Scott McCloud is a sequential imagery theorist and visionary, who through his non-fictional works explored the medium of sequential art and comics in a revolutionary manner. To this day, 20 years after ‘Understanding Comics’ – the first release in a series of 3 analysis books, his sincere breakdown and interpretation of the medium is an outstanding source of influence and revelation for people exploring it, and has unconditionally proved its timelessness. Discovering his works, especially Understanding Comics, has been significantly insightful during the creation process of my final major project.

The term ‘Sequential Art’, or ‘Sequential Imagery’ (the two are often interchanged), was initially coined by comics artist and graphic novel populariser Will Eisner, and explored in his analysis book ‘Comics and Sequential Art’. Even though this release came earlier, I happen to prefer Scott McCloud’s ‘Understanding Comics’ and the way he/it handles the exploration of the medium, due to the utter literary profoundness and ingenuity in his/its presentation.

Since the book is about the philosophy, significance and potential of sequential imagery, he innovatively presented the entire work as a comic, utilising sequential imagery alongside text to fully reveal this medium, and instantly demonstrate it in real-time. In the first chapter, after deliberating the particulars of the medium with a figurative audience within the ‘narrative’, McCloud defines it as “Juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer” (McCloud, 1993). Whilst his definition does summarize technically what the medium is, everything that immediately follows until the very end of the book does so much to further explore in grave detail the brilliance of it, so much so that it is difficult for me to summarise its many aspects without basing an entire essay around it.

When flicking through this book again, I found it very difficult to choose which pages to include here, as every page is simply outstanding. Still, below I have chosen the contents of two specific chapters that represent the reasons for wanting to use this medium and share my understanding of it. I haven’t used much material from the other chapters, as the topics it covers aren’t relevant to my project.

Chapter 2:

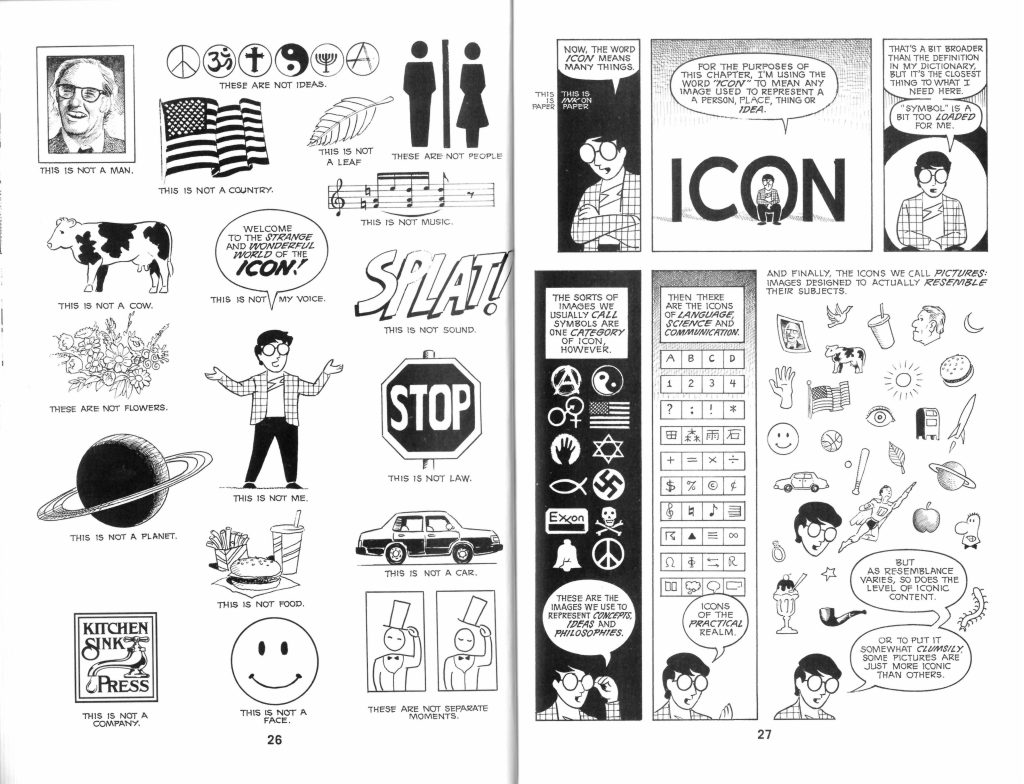

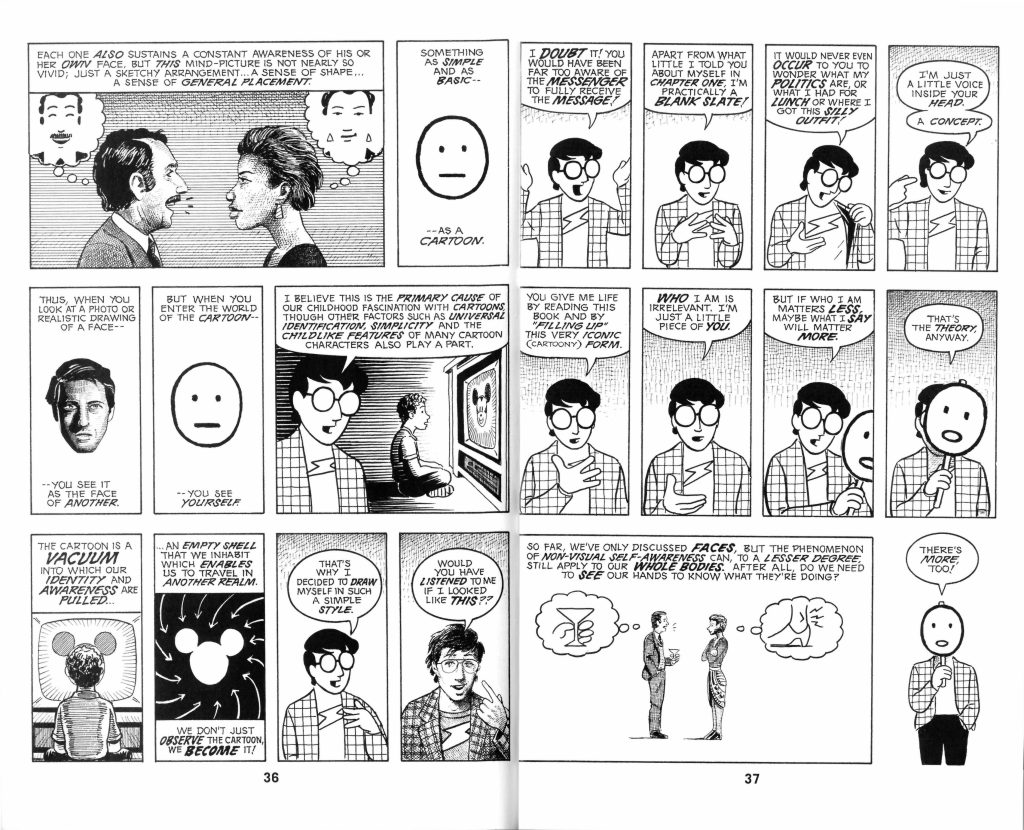

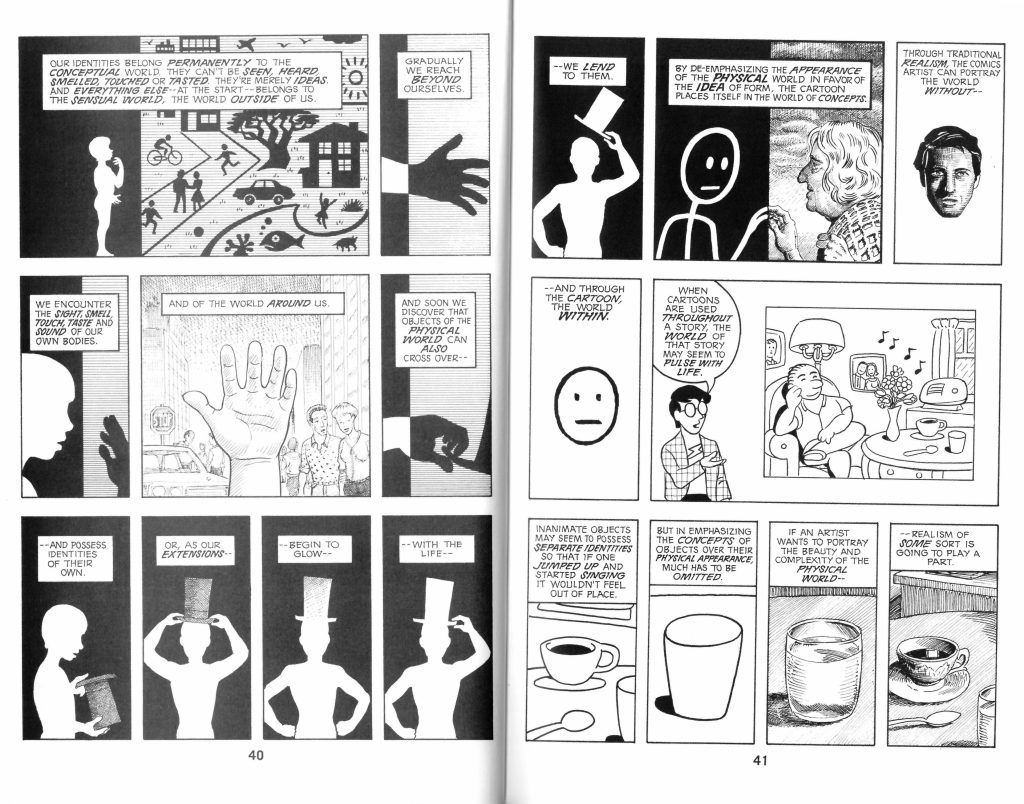

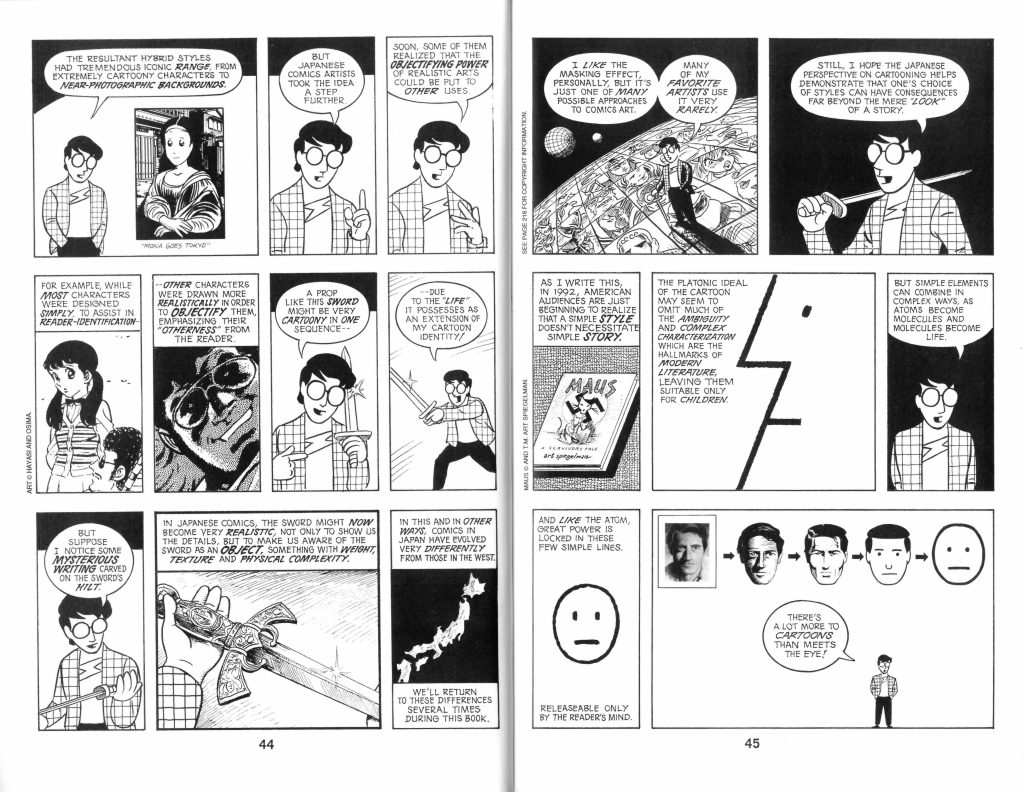

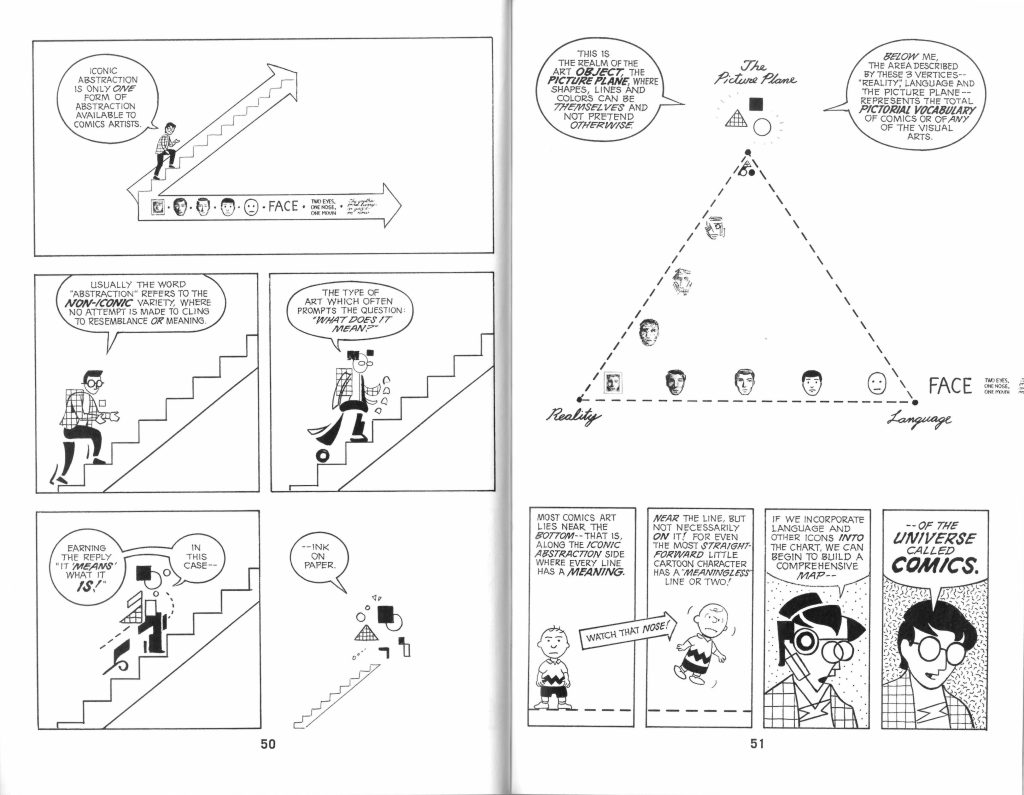

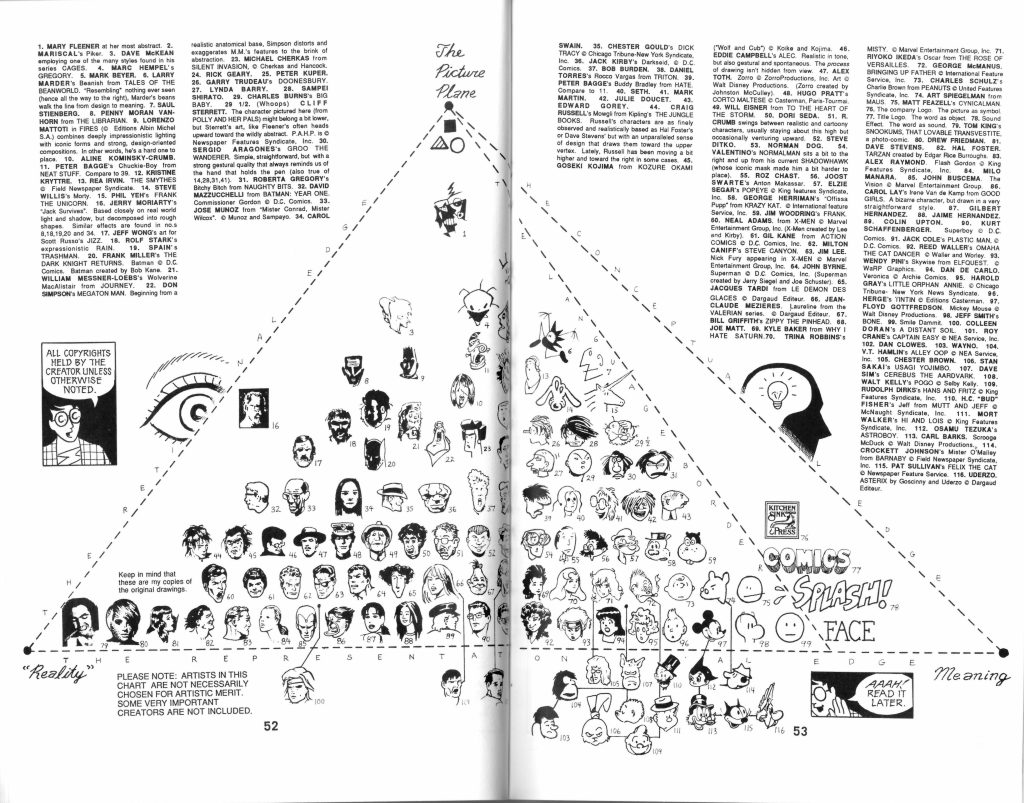

In the second chapter of ‘Understanding Comics’, ‘The Vocabulary of Comics’, McCloud explains that due to the way humans perceive in our imaginations both ourselves and other things we cannot physically see, we internally create in our minds a pictorial representation of that thing comprising of “…a sketchy arrangement… a sense of shape… a sense of general placement. Something as simple and basic– –as a cartoon” (McCloud, 1994), due to our lack of photographic memory. He then goes on to explain that stylisation can have a grander accentuation and impact on ideas and concepts as opposed to realism – “By de-emphasizing the appearance of the physical world in favour of the idea of form, the cartoon places itself in the world of concepts” (McCloud, 1994). This means that pictures, or cartoons, possess the ability to represent and convey something much grander as opposed to something that purely has visual realism applied to it, as the simplicity of said stylisation resonates with human beings’ lack of a photographic memory. This representation can be anything, and no matter how simple it is illustrated it can be easily identifiable to the human eye and mind.

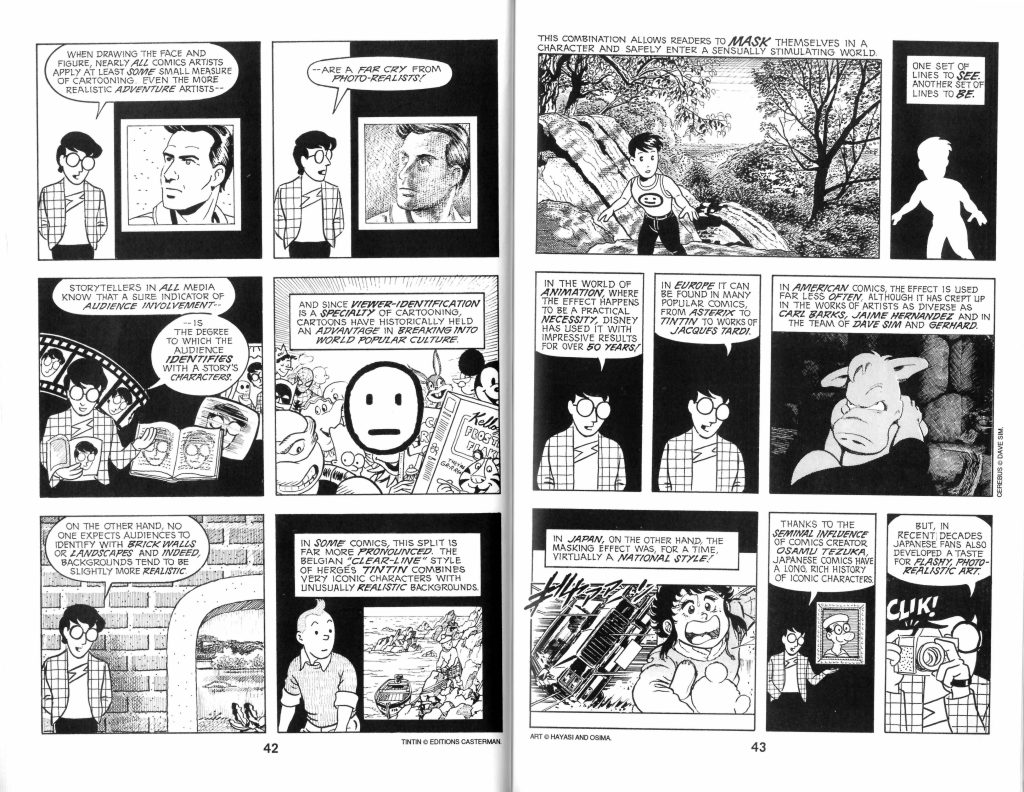

He then furthers this understanding of stylisation against realism by expounding the possibilities of combining and juxtaposing the two together to greater achieve the goal of oneself identifying with the media they are consuming (in this case comics) – “This combination allows readers to mask themselves in a character and safely enter a sensually stimulating world. One set of lines to see. Another set of lines to be” (McCloud, 1994). Here he is referring to how in many pieces of media characters are illustrated with simplicity/stylisation, and are set against a more detailed realism-infused background, as it it allows the viewer to resonate with the character with which they identify easier by alienating what isn’t intended to be identified with (the surrounding environment and objects), thus strengthening the resolution they have with the character. I adore the possibilities of what stylisation can create, and since my project is very personal this is exactly what I want to convey. If time permits, I would love to adopt the use of this approach to stylisation in my work.

Chapter 3:

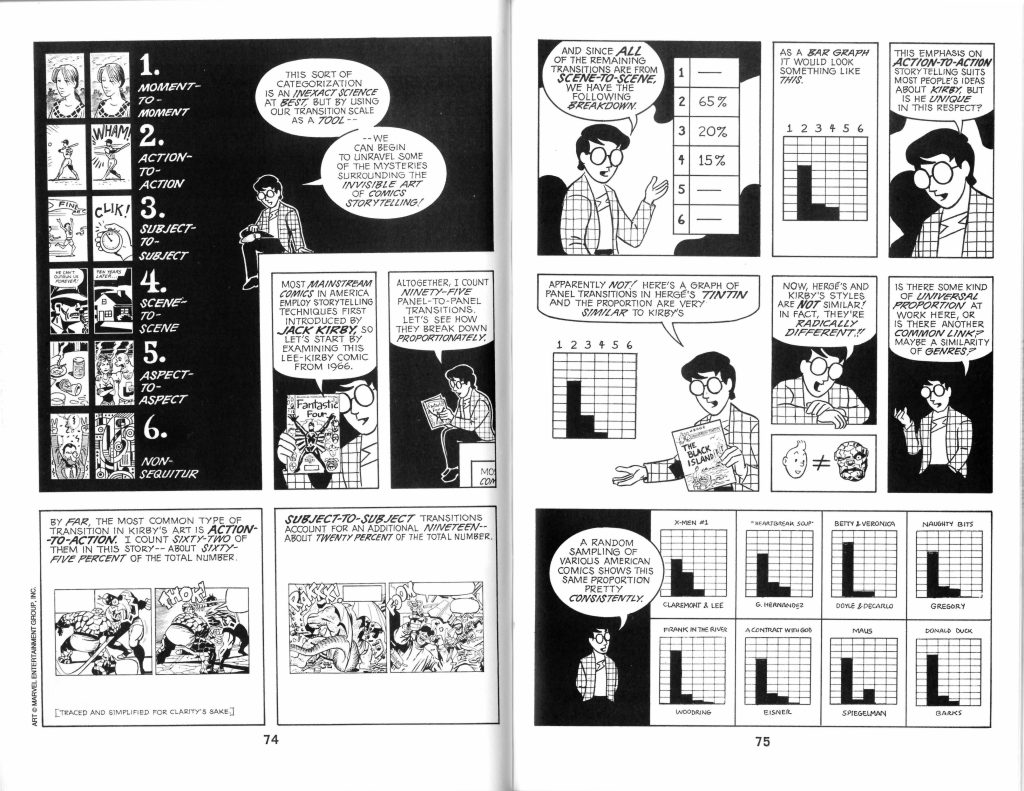

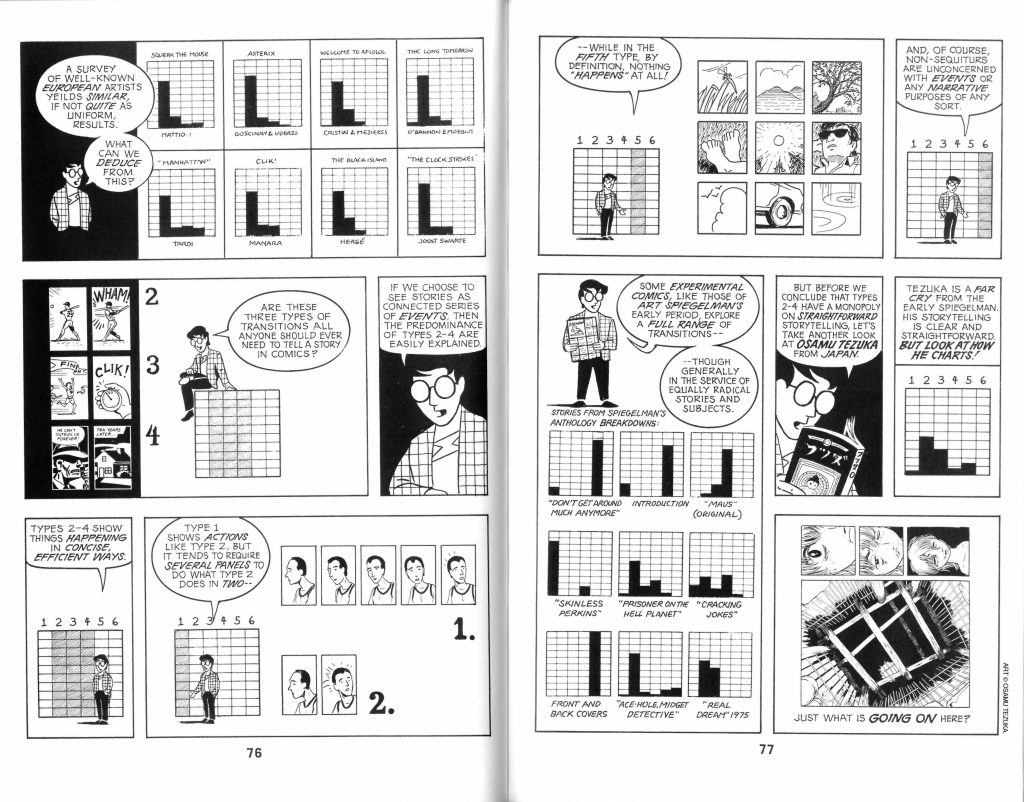

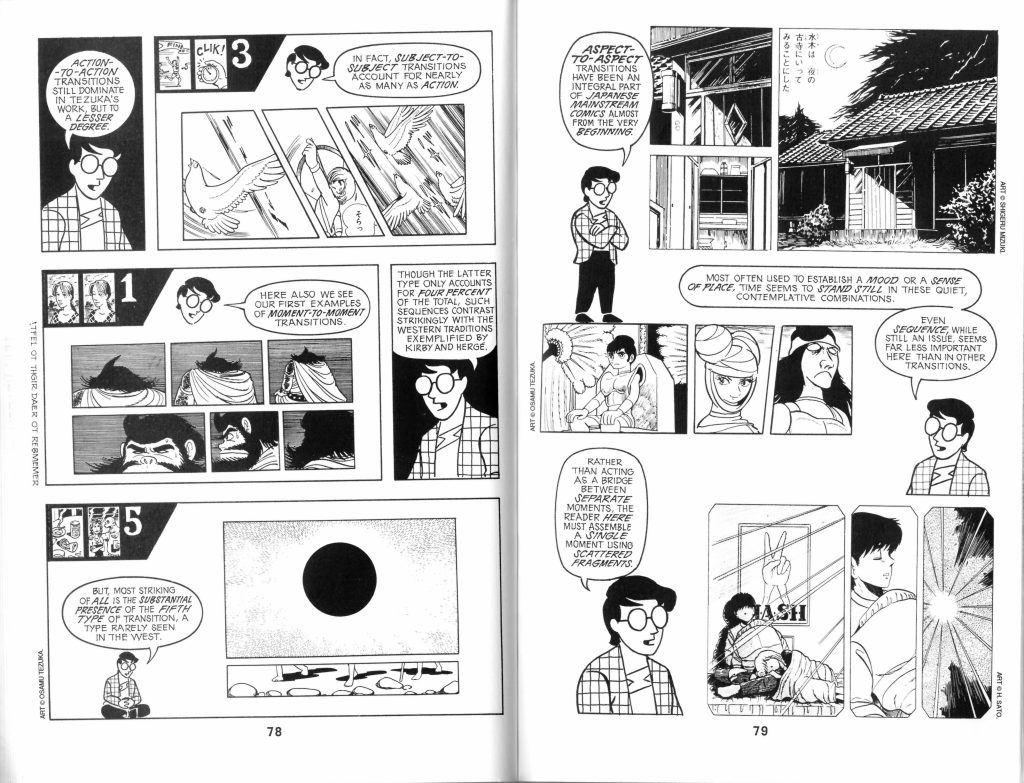

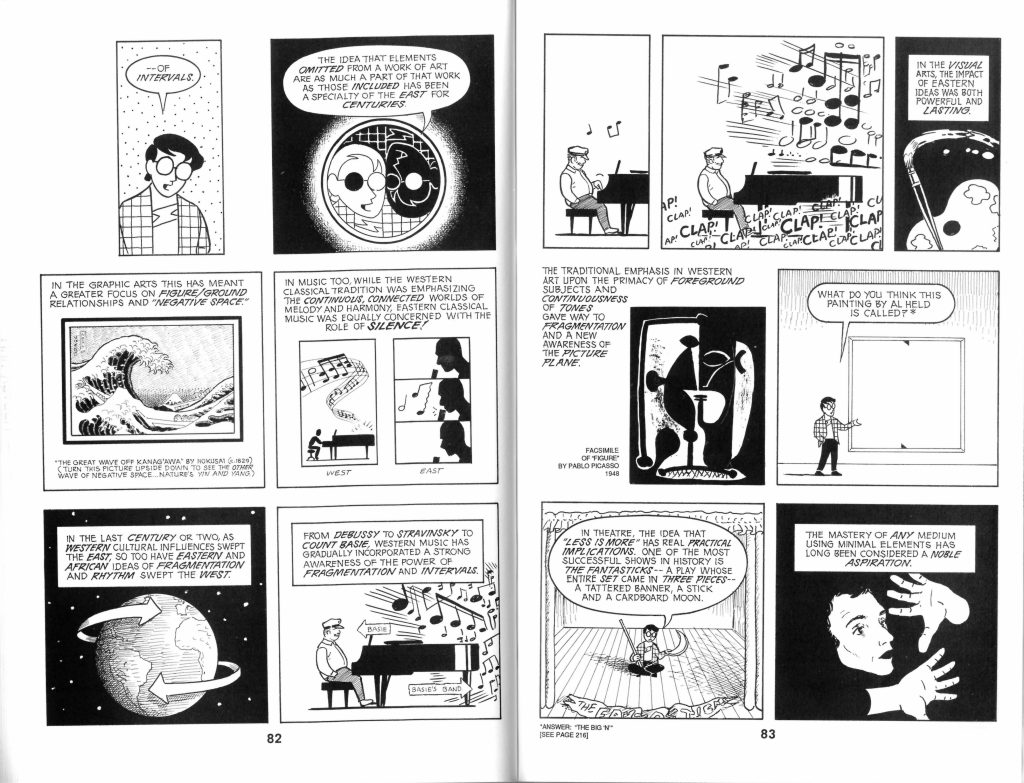

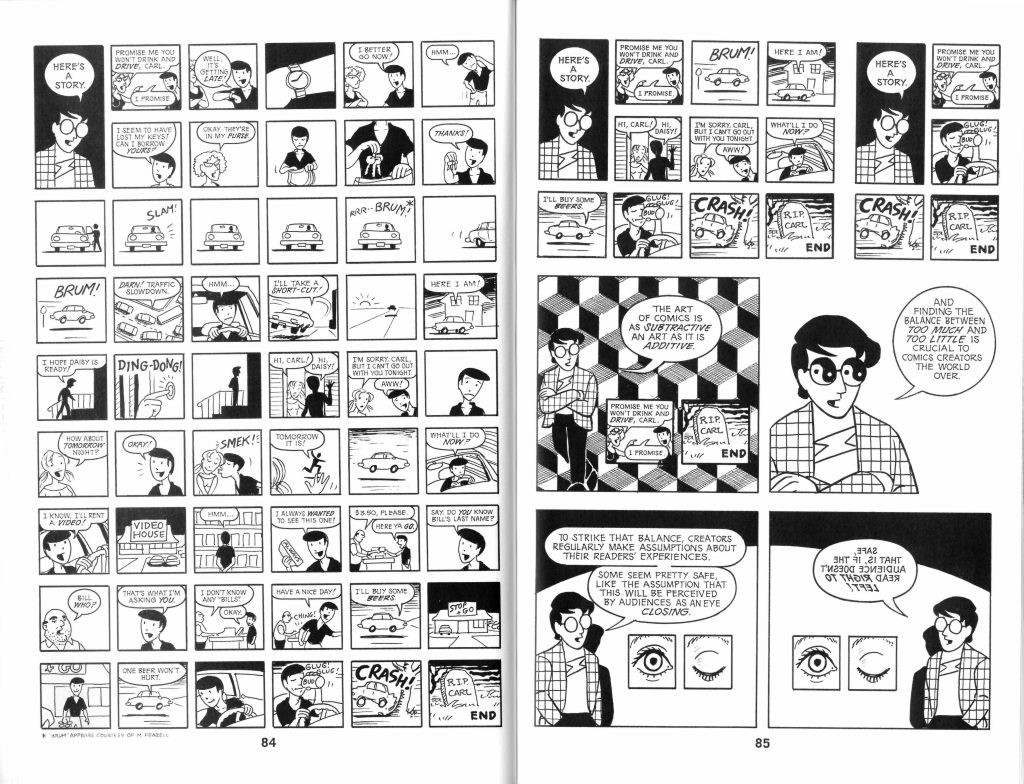

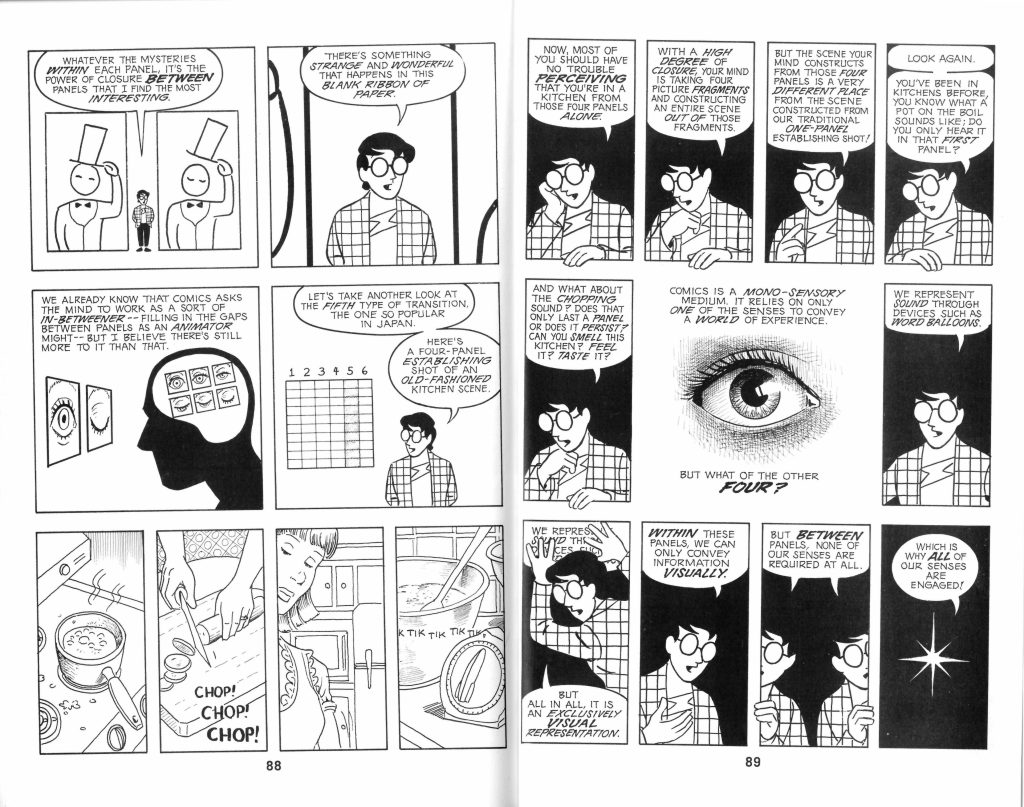

Across the third chapter, ‘Blood in the Gutter’, McCloud discusses sequential art’s visual transitions between what is visually presented within the panels and pages of comics, and categorizes each style depending on visual and differences that take place between them. His categorizations scale between ‘moment-to-moment’, where minimal changes are present, and ‘non-sequitur, where entirely different pictures, themes and ideas appose each other and are seemingly irrelevant. Whilst these can represent the amount of narrative ‘time’ that takes place between two narrative moments, they principally involve what is pictorial/artistically displayed. He then delves into the potential applications of each categorization, and how different sequential art publications from different cultures and backgrounds have differing overall handling of each categorization depending on their style of work.

I would like to incorporate this into my final production by using different transition styles to reflect different emotions. For instance, happiness and contentment would have moment-to-moment transitions applied to reflect my character enjoying being ‘in-the-moment’, and scene-to-scene and aspect-to-aspect would be used for despair and disorientation to reflect panic and time slipping away.

Chapter 5:

I have included one set of pages from the fifth chapter, ‘Living in Line’, as an annex, as it supports my understanding of the use of line to convey emotion from my previous blog post on Nagata Kabi – here McCloud shows different examples of linework to support an intended emotion or feeling.

References:

Quotes and figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14:

McCloud, S. (1994) Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, 2nd edition. New York, USA: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc.